Ballplayer George Burns not forgotten

GLOVERSVILLE — When the name George Burns comes up, thoughts immediately turn to the famous actor and comedian who died in 1996 at the age of 100 —and not to the famous New York Giants outfielder who lived at 5 Orange St. in Gloversville.

There are few people still around who would zoom back in time to the dead-ball era in major league baseball when “Silent George” prowled left field at the Polo Grounds for the New York Giants. He was regarded by legendary manager John McGraw as “one of the most valuable ballplayers that ever wore the uniform of the Giants.”

That George, arguably the original George Burns and the probable source of the name for the entertainer, retired to Gloversville and opened a pool hall at 16 South Main St.

From 1911 to 1921, ballplayer George Burns led the league five times in runs scored, appearing in 19 World Series games and setting a Giants stolen base record (383) that wasn’t broken until Willie Mays did it in 1972. At the same time, the actor/comedian George Burns was just a kid named Nathan Birnbaum, growing up in New York City and apparently paying attention to baseball.

In later years he admitted the choice of his stage name was influenced by the two major leaguers of that era who owned it. There are, however, other versions of the story that say his brother came up with the name George and the surname came from a nearby coal company.

But the case for Gloversville’s George is a strong one. The Giants’ George J. Burns, who turned left field at the Polo Grounds into “Burnsville” while he pioneered the use of sunglasses and stole home 27 times, was in all his glory in the entertainer’s hometown at the time when Birnbaum chose to be Burns. A second ballplayer, George H. Burns, was also playing in those days but in far-off Detroit and Boston. He did, however, finish his career with the Yankees in the late 1920s.

Gloversville resident Michael Hauser is known in the area as a sports show promoter and memorabilia collector; he’s also a descendant of Gloversville’s Burns.

Hauser has collected some important Burns artifacts — such as his glove and a bat —and is displaying them prominently now in the special local baseball exhibit he produced for the Fulton County Museum. Hauser tracked down the glove in Canada where it was in the possession of a collector.

Burns, who was a minor leaguer in his hometown of Utica when the Giants bought his contract for $4,000, shares the exhibit with such other local major leaguers as Giants pitcher Hal “Prince Hal” Schumacher of Dolgeville, the Reds’ Chuck Harmon, Marlins’ World Series manager Jack McKeon, Boston catcher Russell “Bud”Holmes and Detroit pitcher Roger Weaver. Harmon and McKeon played minor league ball for the Glovers.

Successful college players also have space at the exhibit along with minor leaguers Derick Himpsl, a pitcher in the Braves organization, and Mayfield slugger Randy Marshall, a Rangers farmhand. National League President Nicholas Young (1885-1902), whose family owned Fort Johnson, and Hall of Fame pitcher Jack Chesbro, who threw for the Johnstown minor league team in 1895 before moving up to the Highlanders (the precursor to the Yankees) and then the Yankees, will soon be added to the exhibit.

Getting the facts

Hauser has been making Burns into a personal project since 1989 when he traveled to Cooperstown to clear up his own doubts about the veracity of the stories he heard about Burns growing up. “I thought they were exaggerating,” he said of the family’s rendition of the legend.

Since his first visit to the Baseball Hall of Fame, when officials presented him with boxes of information about Silent George, Hauser has returned many times. It became apparent, Hauser said, that “he really did have an unbelievable career . . . he was in the upper echelon of his era.”

Burns may have been a top player but even after his huge contribution to the Giants’World Series victory in 1921, he was paid only $10,000, Hauser discovered. When the Giants traded Burns to Cincinnati before the 1922 season, Burns sought a raise to $12,500, the documents show.

Hauser found a letter from the Giants to the Reds arguing against the higher salary and insisting the Giants would have offered no more than $10,000.

When the Reds played the Giants in 1922, the Giants held George Burns Day and presented him with his World Series honors from the year before along with a diamond-studded watch. After three years in Cincinnati, which included a 1922 exhibition stop in Gloversville, Burns spent a final year with the Phillies and then retired.

Though Burns returned as a Giants coach in the early 1930s, by 1937 city directories show he was running the pool hall and there are news accounts of him playing in local old-timers games.

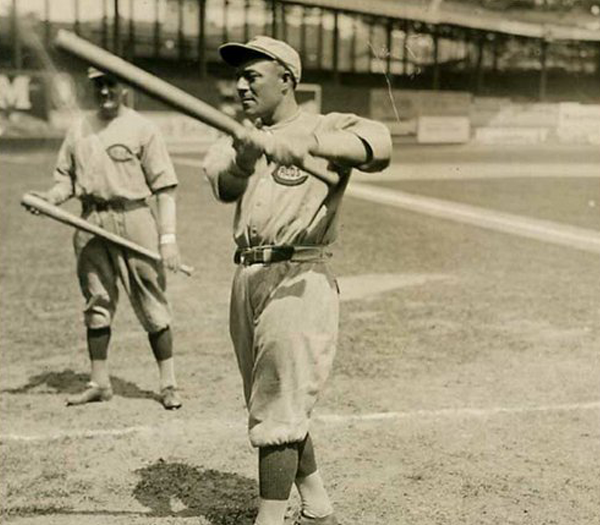

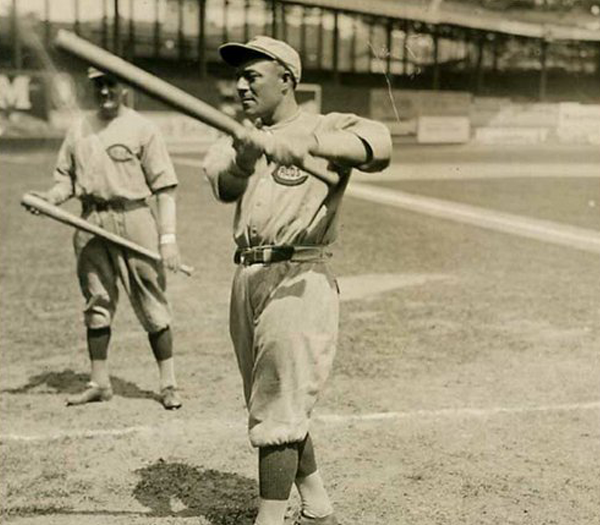

As seen in Hauser’s museum presentation, the New York Herald Tribune caught up with Burns in Gloversville in 1950. Alongside a photo of Burns in his prime with the Giants there is a shot of him at his desk at G. Levor leather company where he worked as a payroll clerk.

He retired in 1957 and died in 1966. Worthy of Hall?

Hauser believes Burns should be in the Hall of Fame and has presented his case to the Hall’s research department. Hauser is not optimistic, although Burns continues to receive a few votes each year from the Veterans Committee.

He compares Burns’ career — in stature for his era —to that of Bernie Williams, another top player who may not make the Hall.

Burns has a lifetime batting average of .287, hit .300 or better three times, scored 1,188 runs including 115 in 1920, collected 2077 hits with 611 RBIs and finished 15 seasons with a .384 slugging percentage. He stole a league-leading 62 bases in 1914 and 40 in 1919.

In the 1921 World Series against the Yankees, Babe Ruth’s first in pinstripes, Ruth’s home run to establish the lead was erased in the eighth inning by Burns’double.

Hall of Fame researcher Gabriel Schechter, the author of a book on the Giants of that era, called Burns “as good an offensive force as they had during that decade.”

As Burns entered the more live-ball era of the 1920s, when power hitting was cherished, “his lack of power was a detriment,”Schechter said.

It was also an era in which players were judged to be past their prime once they turned 30, a mark Burns hit in 1920, Schechter said, explaining why the Giants traded him after one of his most productive seasons.

But, said Schechter, “he was very solid for a decade.” The “runs scored” statistic was highly regarded in that era and Burns was a league leader, Schechter said. The 2,000-plus hits “is nice, but doesn’t stand out.”

Meanwhile, Hauser said, those area sports enthusiasts who enjoy such debates are invited to join the Fulton-Montgomery Sports Historical Society. Contact Hauser at